OR John Kerry Should’ve Grown A Beard: The North-South Manliness Inversion

A Post That Cites Its Sources…with Footnotes!

As I mentioned in the preceding post, the Nick’s Crusade blog is a history blog too. I think delving into history can be very valuable, not just because the strange doglegs and twists in the American story—history NEVER progresses in a straight line—are infinitely interesting, but because we become better thinkers and citizens the more we understand our prologue, the previous generations, the prior struggles, and what we’ve gained and lost since.

One thing we’ve lost—though we have gained from its absence in many ways—is the whole concept of the elite 19th century Southern Gentleman, the image of Southern aristocrats with smooth, un-calloused hands and clean-shaven plump faces, and the brutal slave-driving that made such lifestyles possible. A lot of insight into that old image can be gleaned from the strange story of William Rufus deVane King of Alabama (my home state).

William R. D. King—more typically referred to as just “William R. King”—was the first U.S. Senator from Alabama (alongside John Williams Walker, who was also sent to Washington—the state legislature electing two U.S. Senators per constitutional requirements—after Alabama was admitted to the Union in December 1819). King also played a major role getting Alabama statehood done, and helped write the constitution of Alabama. He named the city of Selma “Selma” meaning “high seat” or “throne” in the 18th century Ossianic poem The Songs of Selma, was president pro tem of the United States Senate, got into a Hamilton-Burr-style duel with Henry Clay,¹ and served as U.S. Minister to France and had other diplomatic posts in Naples and St. Petersburg. As president pro tem of the Senate, he was behind the writing and passage of the Compromise of 1850 and more. What’s odd is, he did all this while being…while being known by the public as super effeminate and flamboyant, and was re-elected again and again by the hardcore states’ righters in Montgomery (prior to the ratification of the 17th amendment in 1913, state legislatures elected U.S. Senators to represent their state).

I won’t say William R. D. King was gay, though it is very striking that, in a culture that almost never mentioned such things, contemporaries like Andrew Jackson publicly called him by derogatory names like “Miss Nancy,” and

powerful Tennessee Dem Aaron Brown (later appointed postmaster general under Buchanan) referred to him as “she” and “Aunt Fancy” and [Buchanan’s] “better half.”² The Senators King and Buchanan were reported walking arm in arm around Washington, though that was common for men even in James Garfield‘s time 30 years later. The rumors of King wearing 18th century powdered wigs and stockings long after they’d been abandoned in the 19th century are false,³ but there was definitely a lot of scandalous gossip in D.C. about his clothes and mannerisms. And it’s well established that King did have a very intimate relationship with future-president James Buchanan, and something must have been unusual enough to’ve drawn derision.  Buchanan was sometimes ridiculed as “Mr. Fancy Pants” or “Granny Buck.”

Buchanan was sometimes ridiculed as “Mr. Fancy Pants” or “Granny Buck.”

Still, the serious historian demands a high standard of proof: the text document equivalent of “pics or it didn’t happen.” Though there is more material suggesting King was seen as gay than almost anyone else in the 19th century, it’d be unwise to say King was a homosexual with certainty. I agree with the James Buchanan entry in glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture that:

In his The Invention of Heterosexuality Jonathan Ned Katz cautions against the application of contemporary terms regarding sexuality to other times and societies in which “[w]ays of ordering the sexes, genders, and sexualities have varied radically.” He further points out that in the “pre-Freudian world [of early-nineteenth-century America], love did not imply eros”–although neither, of course, was an erotic component excluded.⁴

As King’s effeminate manner is evident beyond a shadow of a doubt, I’ll ask a broader—and, I think, more interesting—question, on gender presentation widely-speaking: how is it that such an effeminate public figure got elected by the legislators in rough-and-tumble frontier Alabama?

The answer is, there was nothing odd about William R. D. King amidst the Southern slaver planter aristocracy of his generation. It only seems strange to us, seeing through the lens of the latter half of the 20th century and its mega-strict gender roles. In the antebellum South, the elite planter could be flamboyant, his body unmarked by any of the wear and tear associated with daily labor, his beardless, cherubic visage and opulent clothing a sign of plantation riches, heralding social status as much as signaling the success—and therefore rightness—of the Old South. That kind of presentation harkens back to the aristocratic plantation lifestyles of the 17th and 18th century colonies, when it was, if anything, MORE pronounced. The kind of luxurious appearance and elite manner King exemplified was not uncommon among antebellum aristocrats in cotton country, in fact, flaunting your aristocratic bona fides was cool.

The anti-slavery left, the free soil partisans of the north who were organizing into what would soon be called the Republican Party, had picked up on this. By the time Millard Fillmore—a northerner with pro-slavery sympathies—moved into the White House following President Taylor dying of dysentery in 1850, they had a name for his sort: doughfaces, an obvious allusion to the idle, beardless planter aristocracy.

The best explanation of masculinities of the 19th century and the politics of facial hair I’ve found, is in Adam Goodheart’s amazing book 1861:

It was no accident that Northerners who sympathized with slaveholders were called “doughfaces”: in the American context, beards connoted a certain frank and uncompromising authenticity. Nor was it a coincidence that “Honest Abe” began cultivating his famous beard as he prepared to take over the presidency from “Granny Buck.”⁵

Northern free-soilers began presenting themselves as everything opposed to those they framed as the effete, decadent planter class, or as they referred to them, “the slave party.” They cultivated an image marketed as everything opposite the idle, soft-handed, soft-faced rich Southern aristocrats, they were the candidates of rough-hewn common working men with beards! They [the first decades of Republican Party free soil candidates] were one of the Real ‘Merickens who crawled out of mama and into a log cabin, grew up ridin’ a blue ox and drinking hard cider, and as a man split rails with an axe in one hand while reading law with the other. In the case of Abraham Lincoln, this backstory was kind of true, and his 1860 presidential campaign leveraged that to. the. MAX. The Republican National Convention in Chicago that (unexpectedly) nominated Lincoln for president in 1860 was held in a massive, makeshift wooden “wigwam”—Chicago’s fire marshall didn’t get any sleep that week—and the crowd badgered Honest Abe to tell the convention his “clearing the land with an axe” story…again. The Fall campaign was almost singularly about the image of Lincoln “the rail-splitter,” and was used non-stop; I’m sure some folks didn’t even know his name, just knew “rail-splitter.” To focus on the frontiersmen ethos and related manliness, and all the subtle messages within that, while not mentioning free soil doctrine, abolition, or any of the issues currently boiling over was a brilliant stroke of campaigning genius, and stands out in political history.

Adam Goodheart’s 1861: The Civil War Awakening is the best, most quick-to-understand work of social history I’ve read to date, delving into what Americans lives were really like on the eve of the Civil War. It goes into the BIZARRE social arrangements of 1861 Washington, DC, where free blacks owned slaves, and in Goodheart’s descriptions, those slaves were better off than much of DC’s free black population, who were largely stuck below-subsistence-level in squalid shantytowns, and with no “owner” to vouch for them, they were “undocumented” in a way—my term—and had no real rights to move around in public spaces and were subjected to frequent stops and harassment by police. 1861 has a whole chapter on young James Garfield’s doings at the time, and the way passions were channeled into male friendships in his social circle since expressing emotions was quite circumscribed where women were concerned. I’d like to explore that more in another post.

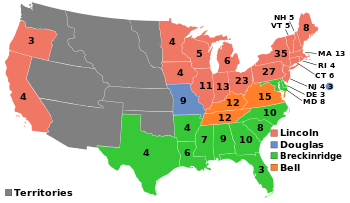

What I discovered by looking back at William R. King vs. early Republican campaigns—and it’s exciting when you figure something out for the first time—is that the North and South have not only undergone a political transformation, there’s been a cultural inversion alongside it.  First, the obvious political inversion. Look at the electoral map following Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 presidential run. The liberal “free soil” north is ruby red, Republican. The South, pro-slavery, is the Democratic Party “solid south,” and with the exception of the fracturing of the Democrats behind several Southern candidates in 1860, then a period of Republican military rule and Republican-elections, “Reconstruction,” the solid Democratic south stays together a remarkably long time, from Andrew Jackson to like… John Kennedy’s run in 1960… Kennedy loses significant votes to Nixon in the Deep South, then in 1972 ALL Southern states peel off—a huge change from the results of the ’68 presidential election just four years before, when the solid south voted for the Dem, Humphrey, and the former-Dem-then-Dem-again, George Wallace—and REALLY break in Nixon’s favor, what with his infamous “southern strategy” and a Dem challenger perceived as wimpy. ’72 clinched the end of realignment, sealed the deal. Ever since, the South has been Republican red, with Dixiecrats like Strom Thurmond and ex-Wallace supporters defecting to the GOP in droves and Lincoln’s states up north increasingly leaning Democratic; it’s a total inversion!

First, the obvious political inversion. Look at the electoral map following Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 presidential run. The liberal “free soil” north is ruby red, Republican. The South, pro-slavery, is the Democratic Party “solid south,” and with the exception of the fracturing of the Democrats behind several Southern candidates in 1860, then a period of Republican military rule and Republican-elections, “Reconstruction,” the solid Democratic south stays together a remarkably long time, from Andrew Jackson to like… John Kennedy’s run in 1960… Kennedy loses significant votes to Nixon in the Deep South, then in 1972 ALL Southern states peel off—a huge change from the results of the ’68 presidential election just four years before, when the solid south voted for the Dem, Humphrey, and the former-Dem-then-Dem-again, George Wallace—and REALLY break in Nixon’s favor, what with his infamous “southern strategy” and a Dem challenger perceived as wimpy. ’72 clinched the end of realignment, sealed the deal. Ever since, the South has been Republican red, with Dixiecrats like Strom Thurmond and ex-Wallace supporters defecting to the GOP in droves and Lincoln’s states up north increasingly leaning Democratic; it’s a total inversion!

What I’ve realized is, it’s also a North-South inversion of the culture of masculinity. In short, northerners are framed as effete, wimpy, decadent, out-of-touch elites today, similar to the way northerners caricatured southerners in the first decades of Whig and Republican campaigns (1840-1870ish). Now, it’s southerners that seem to treasure uber-rigid common man masculinity, and William Rufus deVane King couldn’t get elected dog catcher in today’s Alabama; despite his great wealth, I doubt he could find a place in Alabama public life due to his…different gender presentation. Southerners of today expect a working man to run for office, someone manly and “like us,” the opposite of William R. King. Thomas Frank explored today’s Republican “backlash” against “elites” in his book What’s The Matter With Kansas. This “backlash” is far more determinative than people realize, and deserves much more examination.

John Kerry got the brunt of this backlash in the 2004 campaign, with Karl Rove using the words “effete, elite Massachusetts liberal!” every day. Kerry got Buchanan’ed! Today’s Republicans are as aware of Americans’ deep-seated resentment of “the idle rich” as their northern founders were!

John Kennedy did a modern version of the “Hard Cider Campaign” in 1960; you could call it the “high-ball glass and scotch campaign.” It worked. The “effete, elite Massachusetts liberal!” line was certainly attempted against Kennedy, but for the most part it failed to stick, and he won a majority of working class voters and held the bulk of the South. Kerry failed…failed BADLY to counter the “effete, wimpy, decadent, out-of-touch” frame employed against him. Maybe John Kerry should’ve tried some form of the Kennedy strategy. Maybe he should have gone full Abe, grown a beard and had the press film him chopping firewood.

What he tried instead, photos and videos of him “huntin” backfired terribly, making him look even more phony and out of touch.

Unfortunately, image matters and always has mattered in American politics. Today, it matters disproportionately, and 21st century Democratic candidates like John Kerry have been awful at it. He was completely unable to fight back against the opponent’s framing him as an elite, decadent aristocrat, just as King and Buchanan and other antebellum southern gentlemen were caricatured.

Southern politics and southern masculinity has shifted dramatically, and I wonder if we haven’t lost something important. I wonder if becoming much more rigid in gender expectations isn’t narrowing what’s possible in political life, excluding not just potential 21st century William Rufus Kings, but ANYONE who doesn’t look like a square, iron-jawed working man. We’ve narrowed potential in public life, and I think that’s always bad.

Nick

Footnotes

1. Clay “believed the Globe to be an infamous paper, and its chief editor an infamous man.” King responded that Blair’s character would “compare gloriously” to that of Clay. The Kentucky senator jumped to his feet and shouted, “That is false, it is a slanderous base and cowardly declaration and the senator knows it to be so.” King answered ominously, “Mr. President, I have no reply to make—none whatever. But Mr. Clay deserves a response.” King then wrote out a challenge to a duel and had another senator deliver it to Clay, who belatedly realized what trouble his hasty words had unleashed. As Clay and King selected seconds and prepared for the imminent encounter, the Senate sergeant at arms arrested both men and turned them over to a civil authority. Clay posted a five-thousand-dollar bond as assurance that he would keep the peace, “and particularly towards William R. King.” Each wanted the matter behind him, but King insisted on “an unequivocal apology.” On March 14, 1841, Clay apologized…

Senate Historical Office. “William Rufus King, 13th Vice President (1853).” Senate.gov. (accessed May 6, 2013).

2. p. 189: Hernandez, David. Broken Face in the Mirror: Crooks and Fallen Stars That Look Very Much Like Us. Dorrance Publishing, 2010. http://books.google.com/books?id=OJ-0nNPAisgC&pg=PA189 (accessed May 6, 2013).

3. “Vice President King is sometimes confused with [signer of the Constitution in 1787 and Federalist presidential candidate] Senator Rufus King of New York. This confusion with the first King explains the rumors that persist to this day of the latter King’s wearing of ribbons, scarves and powdered wigs long after they were in fashion. Vice President King always wore the contemporary styles of the early-to-mid-1800s and he never wore a wig.” pp 13-14: Stern, Milton. Harriet Lane, America’s First Lady. 2005. http://books.google.com/books?id=5B9ngDFT2vgC&pg=PA14 (accessed May 7, 2013).

4. Rapp, Linda. glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture. Chicago, IL: glbtq, Inc., 2004. http://www.glbtq.com/social-sciences/buchanan_j,2.html (accessed May 6, 2013).

5. p. 113: Goodheart, Adam. 1861: The Civil War Awakening. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 2011. http://books.google.com/books?id=bCPbnsUPhB0C&pg=PA113